In 2016 ransomware became a multi-million dollar business (see figures 1 and 2). In the first study to achieve end-to-end analysis of the ransomware ‘ecosystem’, research by a collaboration between scientists at NYU, Princeton, UC San Diego, Google and Chainalysis traced ransomware payments through bitcoin for 34 different ransomware families for 2015. At a ‘preview’ presentation of the research results at BlackHat2017, speakers from Google reported the total ransom payments were $25,253,505.

In an extension of the same research – and its formal presentation scheduled for an IEEE conference in May 2018 – the research team report that “In total, we are able to trace $16,322,006 US Dollars in 19,750 likely victim ransom payments for five ransomware families over 22 months”((Huang, D. Y. et al. Tracking Ransomware End-to-end. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, CA, May 2018, 14)) (emphasis added). Their research found that:

- most of the paying victims were probably located in Asia;

- South Korea appeared to be the worst hit, with victims likely to have paid out over $2.5 million in ransoms to Cerber (34% of Cerber’s total revenue identified in the study period) (see figure 3);

- ransomware operators strongly preferred to cash out bitcoin ransom payments at BTC-e, a Bitcoin exchange based in Russia that was taken offline in July 2017 (see figure 4)((Budd, C. Outsourcing crime: How Ransomware-as-a-Service works. TrendMicro (2016). Available at: https://blog.trendmicro.com/outsourcing-crime-how- ransomware-as-a-service-works/.)).

Figure 1: Revenues from ransomware spiked in 2016 as developers found successful ‘business models’((Bursztein, E., McRoberts, K. & Invernizzi, L. Tracking desktop ransomware payments. (2017).)).

Outsourcing crime

Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) is the sale – typically via the Dark Net – of ransomware as a platform integrated with payment processing, to other criminals

who may lack the programming skills to build their own((Budd, C. Outsourcing crime: How Ransomware-as-a-Service works. TrendMicro (2016). Available at: https://blog.trendmicro.com/outsourcing-crime-how- ransomware-as-a-service-works/.)). RaaS ‘kits’((Brenner, B. 5 ransomware as a service (RaaS) kits – SophosLabs investigates. Sophos Labs (2017).)) have become popular since 2017. Examples include Philadelphia, FrozrLocker, RaasBerry, Cerber, Satan, Hostman, Flux and Atom, with monthly ‘subscriptions’ and licenses starting at $39 (see table 1). The ‘features’ are competitive and the costs lower the barrier to entry for would-be cyber criminals, including lone operators and novices who are not part of a larger organised criminal network.

[table id=5 /]

Highwaymen, outsourced bandits and organised brigandary

The practice of holding a person or company to ransom is not at all new: The ‘professionalization’ of highwaymen in Europe was a feature of business and personal risk in the 16th and 17th century. Through the 1970s and 1980s, white- collar extortion and hostage-taking were features of the business landscape in the US: The US authorities issued guidelines to corporations on how to handle such situations.

Criminology research identifies three groups that have benefitted from the age of pervasive IT and internet:

- traditional organised criminal groups which use IT to augment the scale, reach and rate of their ‘real-world’ activities;

- a new ‘breed’ of organised cybercriminal groups which operate exclusively online, using the anonymity afforded by the Dark Net and virtual currencies; and

- organised groups of ideologically and/or politically motivated people who use IT to achieve their objective((Choo, K.-K. R. Organised crime groups in cyberspace: a typology. Trends Organ. Crime 11, 270–295 (2008).)).

The rise of ransomware has popularised the term ‘organised crime’ in company reports and academic research, expanding the concept “to cover profit-driven criminal phenomena occurring completely or partially in cyber-space”((Leukfeldt, E. R., Lavorgna, A. & Kleemans, E. R. Organised Cybercrime or Cybercrime that is Organised? An Assessment of the Conceptualisation of Financial Cybercrime as Organised Crime. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 23, 287–300 (2017).)) . Analysis by BAE Systems (2012) identified a typology of organised criminal networks in cyberspace: swarms, hubs, extended hybrids, clustered hybrids, aggregates, and hierarchies; and concluded that nearly all (80%) of cybercrime is perpetrated by organised criminal networks, arguing that cyberspace augments rather than replaces existing criminal networks. BAE also concluded that the impact and scope of the crime does not correlate with group size; and that many networks are highly transitory.

While the analogies and concepts are helpful in guiding investigators and companies to consider what they are up against, the policy narrative “often assumes a convergence between OC and cybercrime without strong empirical evidence.” This paucity of empirical analysis has important consequences for the overall quality of threat mitigation, because without understanding of the ecosystem we are trying to eradicate, we cannot ever hope to be completely successful.

A study by Dutch and British researchers published in 2017 analysed 40 cases from the Netherlands, Germany, the UK and the US, in which criminal networks acted in cybercrimes that afflicted banks and financial service providers((Leukfeldt, E. R., Lavorgna, A. & Kleemans, E. R. Organised Cybercrime or Cybercrime that is Organised? An Assessment of the Conceptualisation of Financial Cybercrime as Organised Crime. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 23, 287–300 (2017).)). The study was not focused on ransomware per se but its findings are nonetheless important for aiding our collective understanding of the cybercrime world we seek to defeat. The research concluded that:

- None of the analysed networks had a strong hierarchical structure, but all contained dependency relationships and recognisable, differentiated roles;

- In 75% of the evaluated cases, three distinct communities were identified:

- core members;

- ‘enablers’, providing e.g. malware scripting services; and

- money mules. Enablers may work for one or more network and advertise their services in the Dark Net. Money mules may number hundreds and are easily replaceable.

- Detailed information for 68% of the cases showed that the core members comprised s stable group who worked with criminals from other networks from time to time. Groups without a stable core membership used online forums to seek out other suitable members prior to an attack.

- While there was no evidence of violence or corruption using official channels in the cases examined, the evidence for the role of insiders from the legal and financial services is illuminating:

- In 3 cases, bank employees and postal services workers colluded with the criminal gang to provide e.g. account details, increased cash withdrawal limits and redirected mail containing new login details for online accounts;

- In one case, a bank security manager assisted criminals in gaining physical access to the bank premises to place key loggers on the bank’s computers;

- Almost all the analysed cases used legitimate money transfer services and / or virtual currencies.

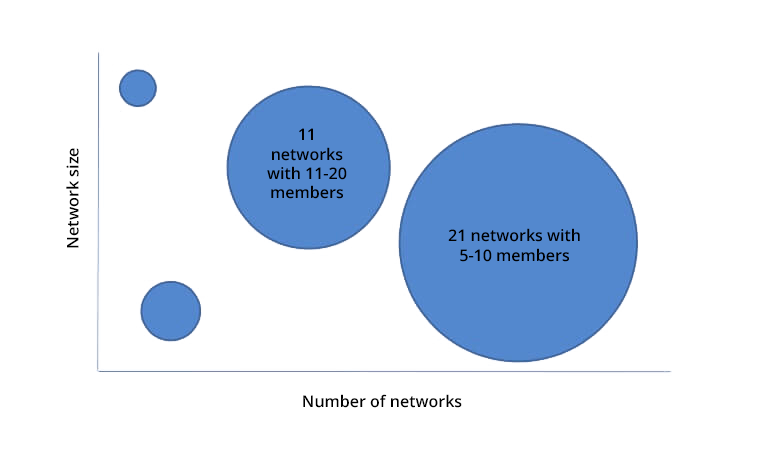

Of the 40 cases, 36 were examined for group size. 21 contained five to 10 core members, 11 had 11 to 20 members; cases with less than four, or more than 21 members, numbered very few (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Estimating size of cyber-criminal networks in Europe

Contrary to their digital world, anonymous image, cybercriminal gangs do not operate in isolation. The social relationships of the analysed groups in this study provide important indicators of where and how cybercrimes could (theoretically) be neutralised. Networks typically fit one of four patterns:

- Formed and grown completely offline through ‘real-world’ social contacts;

- Offline social networks used as a base, specialists recruited through online forums;

- Online forums used as a base, offline social networks used to recruit specialist criminals;

- Formed and grown completely online.

Almost 75% of the cases analysed fit type I or II. The research further concluded that five of the 40 networks analysed had links with well-established, ‘traditional’ offline organised crime groups. These crime families fit one of two roles:

- as the core base, recruiting services from another country to build malware that extends the scope and reach of their offline operations;

- as ‘service providers’ to online groups, e.g. for money laundering and access to fake ID. As in most social networks, the trust relationships were found to be an essential requirement for group cohesion.

The evidence from just these 40 cases suggests that the business of cybercrime is thriving where trust relationships between ‘real-world’ networks and their online counterparts are sufficiently intact for a sustained period during which a ransomware attack can be executed. The centuries-old tactics of highwaymen and organised gangs of thieves find ready translation in the internet age.

However, as the Dutch-UK research team observe, the analysed cases do not fit the definition of organised crime that would meet the minimum sentence requirement in many jurisdictions. This suggests that a revision of criminal acts that don’t yet include the spread and operation of ransomware as a punishable act, is urgently required.