As a tactic for coercing and threatening vulnerable targets into paying up, the technique of professional ransom has a six hundred year history. The advent of cyberspace has created a new environment through which cyber criminals, whether opportunists or organised gangs, can hold the data assets of companies and private individuals for ransom, in distant states and geographies where they are unlikely to face charges anytime soon.

Incidence of ransomware attack has increased through 2016-2017 and looks set to continue, partly due to the easy anonymous payment processing afforded by Bitcoin and other virtual currencies. Unchecked vulnerabilities in IoT and the healthcare industry are likely targets through 2018.

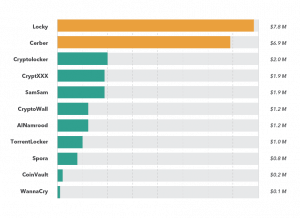

For many companies, it’s easier to pay up than invest in the necessary cybersecurity and data backup actions that can reduce the risk of a successful attack. Ransom payments from 2016-17 for just 34 of the known malware families were at least $22 thousand and with Ransomware As A Service kits starting at just $40, even the most non-technical of criminals can seek a share of the ‘market’, in what is currently a multi-million dollar criminal business.

What is ‘ransomware’?

Ransomware is the result of almost thirty years of innovation by criminals finding ways to monetize malware((Proofpoint. Dialing for dollars – Coinminers appearing as malware components, standalone threats across the web. Proofpoint (2017). Available at: https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/dialing-dollars-coinminers- appearing-malware-components-standalone-threats.)). In a typical attack, a victim’s computer, phone or systems are either locked or encrypted and the ‘ransom’ is the fee (usually in Bitcoin or similar) to release or decrypt the affected systems or files (see figure 1).

The ‘business operations’ methods used in cyber extortion schemes have been known since 1989((Hampton, N. & Baig, Z. A. Ransomware: Emergence of the cyber-extortion menace. (Security Research Institute (SRI), Edith Cowan University, 2015). doi:10.4225/75/57b69aa9d938b)): the aspiring criminal must find a way to demand ransom and process the payout, while remaining undetected. Cryptovirology researchers had proposed ‘“reversible denial of service attack[s]’ in 1996((Hampton, N. & Baig, Z. A. Ransomware: Emergence of the cyber-extortion menace. (Security Research Institute (SRI), Edith Cowan University, 2015). doi:10.4225/75/57b69aa9d938b)) ((Young, A. L. & Yung, M. Cryptovirology: the birth, neglect, and explosion of ransomware. Commun. ACM 60, 24–26 (2017).)), but the tools and methods to mainstream these were not visible until almost a decade later. Malware became a profitable ‘business’ in the early 2000s with the spread of botnets (see figure 2). The first ransomware, Gpcoder, was seen in 2005, encrypting disk content using the methods proposed in 1996. Initially it was easy to break: the code was poorly implemented – but significantly, Gpcoder improved over time.

Scareware, such as fake antivirus, became a money-making scam for cyber- criminals in the mid 2000s, who often had to set up shell companies to process card payments. By 2012, extortion-enabling malware became ‘mainstream’. But to really succeed as a business, ransomware needed three technologies:

- strong, reversible encryption to lock and decrypt files;

- anonymous communication of keys and decryption tools;

- untraceable payments((Hampton, N. & Baig, Z. A. Ransomware: Emergence of the cyber-extortion menace. (Security Research Institute (SRI), Edith Cowan University, 2015). doi:10.4225/75/57b69aa9d938b)).

The first ransomware to successfully demonstrate all three were CryptoLocker, in 2013((CrowdStrike. A deep dive into the evolution of ransomware. (2016).)) and CTB-Locker, in July 2014((Hampton, N. & Baig, Z. A. Ransomware: Emergence of the cyber-extortion menace. (Security Research Institute (SRI), Edith Cowan University, 2015). doi:10.4225/75/57b69aa9d938b)). CTB is an acronym for Curve encryption, Tor browser and Bitcoin.

Bitcoin changed everything.

With the formalisation of Bitcoin as a recognised exchange in 2012 and others soon after, cyber criminals found in cryptocurrencies everything they needed to complete the design of ransomware as a financially-viable business model. Vastly simplifying the ransom payment process (see figure 4), Bitcoin was the paradigm shift that enabled a new threat, Ransomware as a Service (RaaS), to grow rapidly in 2016-17. Criminals lacking the technical skills to build and service their own ransomware could buy ready-made unlimited use packages, many of which include a payments processing system, for as little as $40.

The number of new malware specimens has grown rapidly since 2012 (see figure 5). Today there are at least 409 known families of ransomware: for a list of all known ransomware, see open source data maintained by @cyb3rops [http://goo.gl/b9R8DE].

Some are very fast acting: the ransomware families surveyed by one of the most comprehensive studies to date((Bursztein, E., McRoberts, K. & Invernizzi, L. Tracking desktop ransomware payments. (2017).)) achieve infection to full encryption in under a minute. The latest variants have inbuilt learning, such as avoiding antivirus detection. Particular sectors have been targeted: for example, the City of London experienced at least 10,500 ransomware attacks in 2016((Stuart, A. The rise and rise of ransomware. The Economist Intelligence Unit Perspectives (2016). Available at: https://perspectives.eiu.com/technology- innovation/rise-and-rise-ransomware.)). In 2017, the three most encountered ransomware families on devices using Microsoft operating systems were WannaCrypt, LockScreen (which primarily affects Android but can transfer to synced Windows machines) and Cerber, with devices in Asia the worst hit((Microsoft. Global Security Intelligence Report v.23. Microsoft Security (2018). Available at: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/Intelligence-report.)). Ransomware does not appear to have a specific target geography (see figures 6 and 7), instead using extant network vulnerabilities to locate and infect unpatched operating systems and other unsecured devices.

In the world of cybercrime, ransomware is today a ‘proven business model’. Its success is reflected in the myriad threat analyses released regularly by the world’s leading threat intelligence sources. The three headline issues discussed in Microsoft’s 23rd Security Intelligence Report (March 2018) are the closely related problems of botnets, low-cost / high return cybercrimes and ransomware.

Encrypting and non-encrypting ransomware is generally considered separately from data-wiping malware (‘pay up or we will delete it’), examples of which include Shamoon 2, identified early 2017, which was a campaign targeting the oil industry in Saudi Arabia; and MBR-ONI that targeted Japanese organisations in 2017. WannaCry and Notpetya are also thought to be ransomware masquerading as something else, because data was either not returned or not returnable on pay-out of the ransom((Verizon. 2018 Data Breach Investigations Report. Verizon Enterprise Solutions (2018). Available at: http://www.verizonenterprise.com/verizon-insights- lab/dbir/.)).

On June, 26th 2017 a wiper attack known as NotPetya spread worldwide in what initially appeared to be a ransomware attack. Unlike WannaCry, NotPetya had no kill switch. It steals login credentials and spreads laterally through networks, in a combined client-based / network-based attack that used known vulnerabilities in Windows XP-2008 systems. By the end of June 2017 incidents were reported in Ukraine, Russia, England, France, Norway, Israel, Poland, Germany, Belarus, Lithuania and India. Compromised organisations include banks, telecommunications firms, railways, airports, power plants, government departments, logistics firms, shipping ports and the radiation monitoring stations at Chernobyl.

These two are generally described as ‘distraction’ rather than ‘destruction’ campaigns and are currently thought to be the work of a nation-state, not yet identified, for purposes…

Ransomware on the rise?

In 2017, ransomware comprised about 30% of all the 2,216 confirmed breaches analysed by Verizon((Verizon. 2018 Data Breach Investigations Report. Verizon Enterprise Solutions (2018). Available at: http://www.verizonenterprise.com/verizon-insights- lab/dbir/.)). High profile attacks on supply chains and UK health services in June 2017 brought what was already a known threat vector into the global headlines.

A survey of 1,200 security professionals in 17 countries identified Spain, China, Mexico and Saudi Arabia among the worst hit ((Cyberedge Group, LLC. CyberEdge 2018 Cyberthreat Defense Report. (2018).)). 55% of all organisations surveyed had been targeted by ransomware and half the respondents across all 17 countries reported that they refused to pay the ransom, but managed to successfully recover their data. Almost 20% paid out but did not receive their data.

2017 research by Proofpoint “suggests that the number of new malware strains related to cryptocurrency […] now exceeds the number of one-off, “script kiddie” ransomware strains that had been appearing on a daily basis in 2016 and early 2017. […] we expect it to continue as: 1) cryptocurrencies increase in value; and 2) popular Bitcoin alternatives like Litecoin and Monero remain mineable with desktop PC resources.”((Proofpoint. Dialing for dollars – Coinminers appearing as malware components, standalone threats across the web. Proofpoinpropagatingt (2017). Available at: https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/dialing-dollars-coinminers- appearing-malware-components-standalone-threats.)).

WannaCry and NotPetya made global headlines in the summer of 2017 but as a business model, are ‘impostors’ when compared alongside the ‘incumbents’. Among them, Locky was the first to separate ransomware propagation / hosting from payments and seems to have achieved a commensurate increase in ‘revenues’, compared to its ‘competitors’ (see figure 8).

Targeted and vulnerable sectors

Healthcare

The June 2017 ransomware that jeopardised UK hospitals prompted renewed debate in the medical science community about the value and security of electronic health records (EHR). The failure of EHR((Sittig, D. F., Belmont, E. & Singh, H. Improving the safety of health information technology requires shared responsibility: It is time we all step up. Healthcare (2017). doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.06.004 )) can have very serious, even life- threatening consequences for patients under the care of a hospital where security has been breached – with commensurately higher ransoms possible in this sector.

As two medical doctors so succinctly conclude in a mid-2017 article for the New England Journal of Medicine, “We [doctors] need to educate ourselves about this emerging threat and demand that our software is as up to date as the medicines we prescribe.”((Clarke, R. & Youngstein, T. Cyberattack on Britain’s National Health Service — A Wake-up Call for Modern Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 409–411 (2017).))

Critical Infrastructure (CI) and the Industrial IoT (IIoT)

Until recently, power generation facilities and industrial plants have been ‘air-gapped’ from the internet, focusing security breach mitigation on intruder alert e.g. through the introduction of portable data devices. In the age of IoT, the threat landscape is no longer limited to malware on USB sticks or malicious insiders.

Critical Infrastructure typically has three points of entry((Zimba, A., Wang, Z. & Chen, H. Multi-stage crypto ransomware attacks: A new emerging cyber threat to critical infrastructure and industrial control systems. ICT Express 4, 14–18 (2018).)) for an attacker:

- direct internet connection of devices and sensors in a single facility and/or network;

- corporate network (e.g. communications, health and safety, accounts management);

- third-party services vendors (e.g. suppliers of parts or services, contract staff agencies).

Encrypting ransomware can seek out vulnerable nodes then lock one or more of these networks, or data within these networks, taking the CI (e.g. a power utility) offline (see figure 9).

Figure 9: Ransomware propagating across an industrial utility (adapted from Zimba et al. 2017((Zimba, A., Wang, Z. & Chen, H. Multi-stage crypto ransomware attacks: A new emerging cyber threat to critical infrastructure and industrial control systems. ICT Express 4, 14–18 (2018).))). This is a very basic summary of how NotPetya disabled logistics companies in June 2017.

The IIoT is projected to add as much as $14.2 trillion to the global economy by 2023. Each of the sectors set to benefit from the IoT have a duty of care to mitigate the risks associated with enabling pervasive connection across services and supply chains. The domains served by the IIoT affect every aspect of civilian life, including in populations that are not currently served by an internet connection:

- Food supply chains: from monitoring production using e.g. drones and satellite to achieving ever-faster processing and distribution, internet- connected devices and networks are already prevalent in our food chain;

- Emergency response: regional early warning systems (EWS) e.g. in southeast Asia for tsunami early warning can be manipulated to hold a country to ransom;

- Healthcare services: increasing demand for personalised medicine, the promise of cost efficiencies achieved through automated inventory tracking and networked access to Electronic Health Records (EHR) all benefit from the IIoT but also increase the attack surface for criminals who specialise in playing on emotion to coerce a payment:

- Mining: IIoT have a positive role in improved mining safety and natural disaster response, but increased connectivity also raises the possibility for false alarm;

- Transport: particularly in dense urban populations, sensors and traffic- monitoring devices are already a common feature of public transport systems in dense urban populations. A faked chemical attack signature or radiation warning could hold an entire city to ransom.

- Logistics: consumers apparently want an ever-growing range of stuff tracked and delivered faster, while commercial cargoes ship the natural resources that power our economies. About 84% of global commercial trade in goods and energy supplies is via the world’s vast shipping networks. The prospective ransoms in this sector are enormous and relatively easy to execute e.g. through “GPS jamming, spoofing or scrambling could be used to manipulate ships or threaten to run them aground”((Urquhart, L. & McAuley, D. Avoiding the internet of insecure industrial things. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. (2018). doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2017.12.004)).

Cyber attacks in the utility and shipping industries are already known, providing a basis for future threat mitigation. Criminals posing as legitimate operatorsi have successfully infiltrated ports, rigs, cargo firms and finance companies to disrupt services, monitor operations and steal information: for example, in 2014, hackers successfully tilted an oil rig off the coast of west Africa, forcing it to shut down for seven days;. In January 2014, a sustained attack was discovered in which criminals had stolen data and credentials from a firm registered in Spain for defrauding oil brokers; and from 2011-2013, an attack on the Port of Antwerp remained undetected, during which time hackers assisted a criminal gang to identify the containers carrying hidden consignments of drugs.

The road to the future is dangerous

The vulnerabilities created by an internet-enabled world and augmented by an increasingly pervasive IoT, are currently limited only by the imagination of those who seek to profit from ransom.

A report published by the United Nations University in 2017 predicts that by 2050, we will see a return to the power enjoyed by organised crime during the Renaissance, with criminal groups using “the extraction of criminal rents to play an important role in local, national and, in some areas, global governance […serving as de facto rulers in] communities, supply-chains, or markets—not only providing protection and services, but also dictating norms and offering meaning and identity to citizens.”((Cockayne, J. & Roth, A. Crooked States: How organized crime and corruption will impact governance in 2050 and what states can – and should – do about it now. 47 (United Nations University, 2017).)) Seven forces will shape a world of extremes (see figure 10). The scenarios are bleak, but realistic. Indeed, we are already witnessing the extremes of wealth and poverty, climate and resource competition that the report describes.

Figure 10: A dangerous world? Projection of the seven major forces shaping the world in 2050, which together are the future ecosystem for organised cybercrime. (Adapted from Cockayne and Roth, 2017((Cockayne, J. & Roth, A. Crooked States: How organized crime and corruption will impact governance in 2050 and what states can – and should – do about it now. 47 (United Nations University, 2017).))).

This is a future in which the rule of law no longer has authority and the market rewards the most powerful or influential. In cyberspace, power is accrued through the ability to manipulate data, devices and networks. For organised crime and opportunists alike, cyberspace in its current form is just the next market of opportunity.

Where laws become increasingly difficult to enforce, criminals have the upper hand.

Conclusions

Cybercrminals are arguably not to blame for the rapid rise and apparent success of ransomware: they are simply exploiting a market opportunity created by tools and algorithms that were designed for another purpose.

Protection from the scourge of ransomware is not difficult or expensive, but fighting an attack is. Corporate protection playbooks need to be rewritten for the digital age. The human skills and tactics that contributed to the success of banditry in the 16th and 17th centuries remain unchanged in the internet age: the difference is the scale and reach afforded by unsecured networks, a rapidly growing attack surface and the advent of virtual currencies.

While the tactics and trust networks in organised crime remain largely unchanged, unlike ransom-seekers of the pre-internet era, today’s cyber criminals can operate from any location and their networks may be partially on and offline. The grey areas in response by law enforcement include problems of jurisdiction and precedent, which slows the time intervals between incident, attribution and prosecution.

The extremes of wealth, climate and human security that are likely to characterise our future world create an environment suited to survival of the fittest. If the current erosion of trust in knowledge and state continues, the time for survival of the wisest will soon be past.

Like rebuilding a ship that is already sailing, we navigate and rely upon the nascent modern cyberspace at great personal risk. If cryptocurrencies, IoT and commercialised machine learning had been subjected to the same risk and safety audit as our airplanes, cars and medicines, the current ecosystem might not be quite so favourable for criminals.